Walking the Figure 8

Repetition and Return in Elliott’s Smith’s Most Expansive Album

By Alexia Heasley

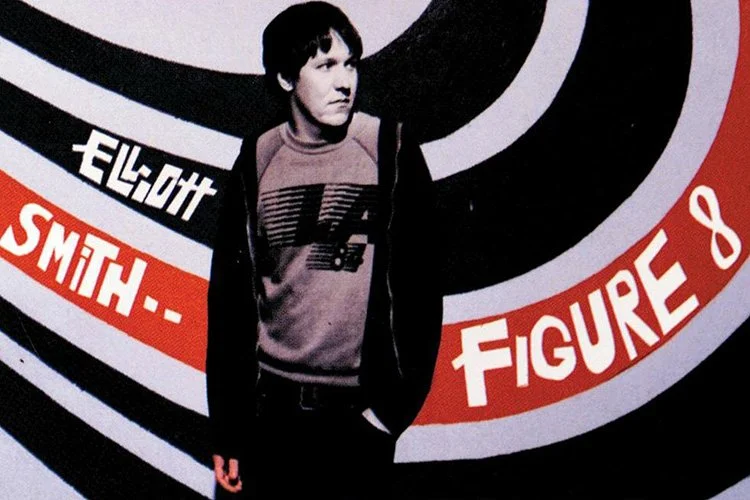

Elliott Smith stands frozen against a painted mural on Sunset Boulevard, framed by an endless, looping trail. His 2000 album, Figure 8, is often considered his most expansive work but the image behind him comes to define the album as an act of return rather than progress. Just three years prior, Smith had recorded most of Either/Or (1997) in his house using an 8-track recorder, a few microphones, a compressor, and a digital effects box he had to program himself. Figure 8 was then recorded across five studios, including London’s Abbey Road. The composition of the tracks suddenly became richer, crowded with layered guitars and full drum arrangements that marked a departure from his earlier albums textured by simpler acoustic sound.

On first listen, the elevated production of Figure 8 seemed to suggest a forward motion, embracing new technological possibilities that could alter his music entirely. However, the title signals otherwise. Elliott Smith makes clear that his music remains steeped in familiarity and return. Its chord progressions circle, its melodies recur with a nostalgic intimacy, and its lyrics remain absorbed by the same melancholic ponderings. The opening track, ‘Son of Sam’, introduces a false tension to the album that becomes slowly undone as the album progresses. The combined piano and guitar, so familiar to Smith’s earlier work, open the first 15 seconds of the song, generating momentum before the drums build and then come crashing in, the unfamiliar companion to that familiar voice. Guided by the percussion, Smith sings with a new assertion that contradicts the melancholy of his lyrics. The song establishes Figure 8’s central preoccupation: motion mistaken for progress. The following track, ‘Somebody That I Used To Know’, draws the listener back into the safety of pure acoustic pleasure, restoring the intimacy of those soft, mellow lyrics without the energetic distraction.

Across Figure 8, repetition is carefully organised to mirror the album’s message. The fourth track, ‘Everything Reminds Me Of Her’, is consumed by a descending chord pattern that never resolves outward, repeatedly folding back on itself to mirror the song’s lyrical fixation. Each return compulsively draws back to the same emotional centre, to ‘Her’. The song traces the figure eight pattern in Smith’s mind, obsessively seeking the comfort of return in focus and in sound. Though Figure 8 is often considered the most stylistically distinct album, Smith works to retain familiarity and comfort in his sound. The electric guitar does not force the song into a new era, but holds it in a suspended emotional present. Technological expansion is balanced with the unchanging state of heartache that Elliott continues to sing of so convincingly.

The compulsion towards repetition carries an almost Freudian quality, reflecting the psyche’s drive to return to unresolved emotions. Smith’s cyclical chord sequences and repeated melodies insist on returning to their starting points. And while they may sound similar, they are subtly altered by what occurs between repetitions, allowing growth even through return. The album works very similarly. Smith’s voice, style, and emotional message remain recognisable throughout, but are refracted through technological progressions and richer arrangements that permanently change their context.

The fifteenth and penultimate track, ‘Can’t Make a Sound’, presents this contradiction most distinctly. The song unfolds gradually, introducing first the simultaneous guitar and vocals, then the rising layers of percussion and instrumentation, building towards a climactic orchestral swell. All the while, the lyrics move in the opposite direction. Framed as a silent movie, Smith repeatedly insists he “can’t make a sound,” an ironic play on the words voiced eleven times in the song. Twenty seconds from the end, the percussion falls out, leaving behind a triumphant horn section to dissolve the song before the entirely instrumental closing number: ‘Bye’. It seems the silent movie has now taken over, leaving Elliott truly unable to “make a sound.” The arrangement has expanded but the psyche has not progressed with it, trapped in the loop of repeated mistakes. With the album’s closure, his lyrics are left feeling unresolved, an intentional absence of catharsis.

It is only in the absence of vocals in the final song that the double-tracked vocals heard throughout the album become so obvious. The doubled voice effect creates a subtle echo, as though it is Elliott’s mind speaking out before his voice catches up. We are confronted by the internal and external workings of his mind, an argument between the self. On Figure 8, the lyrics restrain the instrumental growth surrounding them. Their melancholic continuity preserves the album’s familiarity, but they confine Elliott Smith to walk the same emotional loop, tracing the figure eight again and again.

The album’s cover shows Elliott Smith standing against the Figure 8 Wall on Sunset Boulevard, a mural that has since become an unofficial memorial following his death in 2003. Fans continue to return to the wall, leaving handwritten messages, lyrics, and tributes. The wall preserves the legacy of the album, encouraging the act of return. Nickolas Rossi’s 2014 documentary, Heaven Adores You, embraces the same practice, returning to the wall as a physical anchor for Smith’s legacy, treating it as a modern-day pilgrimage site. The album’s structure of return becomes beautifully instituted through its afterlife. Figure 8 stands apart in Smith’s discography. It may be his most expansive album but it is oriented towards persistence rather than change. His lyrics pass through the same emotional centre over and over, until repetition becomes ingrained within the music, regardless of the new equipment or instruments introduced. So when Elliott Smith waves ‘Bye’ with his final track, I would advise you not to stop there, but to return to the album’s beginning once more and lose yourself in its repetition.