Tropicália: cultural cannibalism as resistance in 60s Brazil

By Liliana Potter

In the shadow of a military coup in late-1960s Brazil, the cultural cross-pollination of a short-lived musical movement spoke truth to power.

The Tropicália movement got its name from an immersive art installation by Hélio Oiticica; the installation’s white sand and potted palm trees distil a superficial view of Brazil as a tropical paradise, before turning it on its head with the words “PURITY IS A MYTH” inscribed inside a brightly painted wooden hut.

Rejection of this purity myth is Tropicália’s lifeforce, with its music embracing pluralism and chaos. Samba, psychedelia, baroque pop, avant-garde poetry and rock ‘n’ roll all are recycled into Brazil’s new countercultural sound, whose elliptical lyrics and genre-warping forms allowed their subversion to sneak past government censorship as they shook pop’s foundations.

A fundamental of Tropicália is the concept of anthropophagy, or cultural cannibalism - the indiscriminate stirring of Brazilian and Western musical influences, high and low cultural touchstones, into a playfully anarchic stone soup of a whole. The Tupinambá indigenous people of Brazil are alleged (by captured 16th century European explorers who survived to tell the tale) to have ritually cannibalised captured Portuguese enemies, ingesting the power and identity of the devoured with their flesh. 1928’s Manifesto Antropófago (Anthropophagic Manifesto) pays tribute:

Tupi or not Tupi: that is the question

As the Tupinambá ingest the oppressor’s power through cannibalism, Tropicália ingests cultural power - Western influences are not merely referenced, they’re recycled, their power seized. At this point (1968), dialogue between Brazilian and Western culture was subversive, even to the left. Nationalism pervaded in two strains: the traditional, fascistic right as enforced by the military dictatorship, and the anti-imperialist national pride of the left, perceiving rock’n’roll and the Americanization of Brazilian music as a threat to its authenticity. Either way, when Gilberto Gil took to the stage of a national song contest ripping Hendrix riffs on an electric guitar while singing in Portuguese, it was a rotten tomato-worthy offence. At the same contest, Caetano Veloso (the second, more flamboyant vanguard of the movement) swung his hips around dressed in electrical cables, green plastic and animal teeth, hair long and androgynous. When the crowd turned their back, he yelled out ‘what kind of youth is this?’

Tropicália’s banquet spread extends equally to the Brazilian music preceding it, particularly posing it as a successor to bossa nova. Bossa nova was the Brazilian genre du jour of the 50s - popularised by the legendary João Gilberto, bossa streamlined and slowed samba rhythms for classical guitar, overlaying them with serene, impressionistic harmony and vocals. This style arguably gentrified Afro-Brazilian samba, and had success in making it palatable to gringos - to this day its big hit, The Girl from Ipanema, is thought to be the second most recorded pop song in history. But against the backdrop of a military dictatorship’s horrors in the 60s, the blithe, apolitical delicacy of bossa’s cool jazz was an ill fit for the fury of the Brazilian left. Bossa is so terminally chill as to be heard most often in the background, as “elevator music” - it wasn’t going to soundtrack a revolution. In contrast to the cocktail bar middle-classness of bossa nova, Tropicália was riotous, imperfect, often eccentric for eccentricity’s sake.

The movement is epitomised by the 1968 album/manifesto Tropicália - Ou Panis et Circenses, a collaboration between Brazilian pop titans Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes, Nara Leão and Gal Costa. In lyrics as well as form, cannibalism and consumption show up often. The USA-supported dictatorship was posed as an economic regeneration for Brazil, prioritising rapid growth and development as freedom of speech was stifled and dissidents tortured. Ridiculing this rising tide of consumer culture was an act of resistance - the album’s title (‘Tropicália, or Bread and Circuses’) can be taken either to cast Tropicália as an antidote to populism’s consumption as a distraction, or perhaps as a nihilistic tongue-in-cheek jab at the ineffectiveness of pop culture to evoke meaningful change:

I freed the tigers and the lions in the yard

But the people in the dining hall

Are busy being born and dying

To get past the government’s censors, Tropicália’s subversiveness is necessarily inventive. Cloaked in oblique lyrical symbolism, a rebellious current runs through the cracks of the permissible.

The dreamy heights of adoration reached by Gal Costa’s Baby mask a satirical edge. The word Baby is repeated in English, among a word salad of products which paint Gal’s starry-eyed romantic persona as equally enraptured by consumerist iconography and her lover:

You have to know more about the swimming pool

About margarine

About Caroline

About gasoline

The closer, Hino Do Senhor do Bomfim, gets interesting: a traditional Catholic song of praise is first played straight as a Sgt. Pepper’s-esque military march, giving way to a breeze of bossa nova bliss for a verse before ending in a jarring half minute of screaming and bomb-blast drums. Here it’s the song’s arrangement, by Rogério Duprat, which narrates the power struggle between tradition and modernity, a bloody battle whose victor is uncertain.

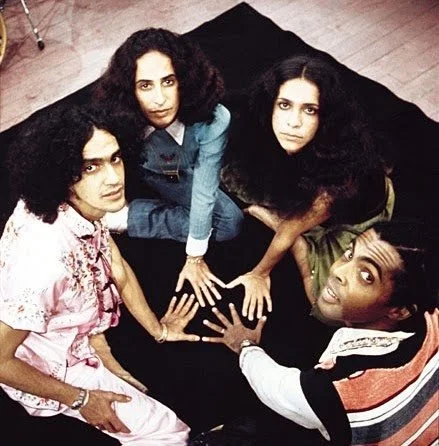

That’s Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil on the front right and left, with Maria Bethânia (Veloso’s sister, fun fact) and Gal Costa behind them.

Tropicália wasn’t to last. December 1968 saw the dictatorship’s imposition of “Institutional Act #5”, viciously cracking down on any artistic expression which could be considered anti-government, and enabling arrests without charge. Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil woke up to their apartments being raided by police; Veloso’s long hair was shorn. The two leading lights of Tropicálismo were forced into exile, bringing the movement to an abrupt end.

Within the year of 1968, tropicália had exploded onto the scene and been snuffed out. It’s an exuberant, overwhelmingly life-affirming music, surging with an inventive vitality in defiance of the circumstances which saw its rise.

Tropicália listening list

Tropicália - Caetano Veloso

Lost in the Paradise - Gal Costa

Miserere Nobis - Gilberto Gil

Trem Fantasma - Os Mutantes

Baby - Gal Costa, Caetano Veloso

Mistério do Planeta - Novos Baianos

International Colouring Contest - Stereolab