The Wolves regress, but now gracefully

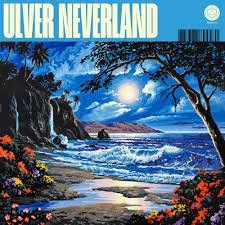

Neverland by Ulver

By Jakub Brzozowski

The Norwegian band Ulver might very well be one of the most experimental outfits to ever reach a certain commercial prominence. Not in the sense that their music won the contests for the most avant-garde piece of art created in the last 30 years. Rather, they never stopped seeking to reinvent themselves release after release.

Briefly, The Wolves (Ulver – a wolf, Norwegian) had started in the early 1990s as one of the more unorthodox of the pagan hordes, which came to prominence during the second wave of black metal in Norway (check out Bergtatt and Nattens Madrigal, if interested). In this period they also made a detour into Norwegian folk with the 1996 record Kveldsanger. The year 1999 signified a foray into electronic music (Themes from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell), which was still placed within an extreme metal context. The next year, however, saw Perdition City, a fully pronounced response to the experimental electronica of bands like Coil, Autechre(and even Norwegian nu jazz outfit Jaga Jazzist. They released a number of EPs in the next few years, which foreshadowed a more megalomaniac approach with the 2005’s Blood Inside. Its successor – Shadows of the Sun stripped the excess in favour of a more minimalistic, chamber-music approach, in the vein of Dead Can Dance. This is a flawless record, and my personal favourite of theirs, with a unique atmosphere, on par with their musical hero’s Coil’s Musick to Play in the Dark duology.

The 2010s were vastly less exciting than what came earlier. The band reached for the naïve psychedelia of the late 1960s (Wars of the Roses, Childhood’s End), mastered their orchestral ambitions (Messe I.X-VI.X), failing to drone with its gods [Terrestrials with Sunn O)))], and finally coming back to their earliest musical fascination: Depeche Mode and, more broadly, synthpop. I’m personally not a fan of the genre at all, but 2017’s The Assassination of Julius Caesar was undeniably a great record, far more experimental and unique than any typical synthpop ordeal. The second instalment in that vein: Flowers of Evil failed to achieve the same heights and felt derivative, whereas the third one – Liminal Animals is an impolite joke. At that point, frankly I gave up on the band altogether and when the first singles for Neverland arrived I didn’t even bother to listen. And so I was unprepared to be proven wrong, as I concede, that Ulver did manage to genuinely surprise me and release their best effort in the last decade.

There is a maverick quality to this album, firstly: its release date is 31st of December 2025. A cunning way to avoid the majority of the end-of-the-year lists? Absolutely and righteously so. But more importantly – musically the band de facto regresses, while it might seem that they evolve yet again. This statement seems completely counterintuitive, but I’ll explain it in a second. In Ulver’s time axis this album lands next to Perdition City, 25 years ago to be exact. The record is a spiritual cousin to the 2000’s watershed album, with all the key components present: emphasis on ambience, spoken word passages, subtle rhythmic undertones derived from techno, experimental synth textures, and cold, alien, urban atmosphere. In terms of genres offered we have that characteristic blend of post-industrial sensibilities with elements of IDM, trip hop, ambient, even dark jazz. These sounds do come off (especially to untrained ears) as unambiguously futuristic and deeply innovative, while for The Wolves and their fanbase, this might be a fractionally backward, slightly nostalgic step.

The paradoxicality of such innovativeness is also present on two other levels. Firstly, the fact that Ulver has somewhat shifted their sound was met with a positive and surprised response. No one really thought that they would try out something else, given that they were producing synthpop for the last 10 (!) years. In a broader perspective, however, this latest stage of their career feels like them at their most unnatural, which is very atypical in the grand scheme of things. Overall, this time in Ulver’s career feels like an unusual period of waiting while internally monologuing “when will they stir the pot again and try out something radically new?”

The second aspect of the paradox is that they came full circle. Let me explain: in their journey into synthpop they deliberately came back to the sounds and aesthetics of the 1980s. Fortunately, not in a cliched nostalgic way – after all, their synth-based music did not feel like a cosplay, but an acknowledgement of the era was undeniable. Now that with this latest album they opened themselves up (again) for some 90s IDM/techno references it might seem that they are progressing. Technically they indeed are, but in reality not really, since they worked within this framework a quarter of century ago.

As for the music itself, Neverland feels far more improvised and free-flowing than the aforementioned comparison point – Perdition City. While the latter contains songs oftentimes reaching for 7 minutes and is a completely all-encompassing immersive experience. With tracks like ‘Lost in Moments’, which reflects the unrelenting bustle of urban lifestyle, or others like ‘Dead City Centres’, that portray a city that is distant and alien to the needs of a human being. Conversely, Neverland opts for shorter song lengths that reflect a specific state of mind and a creative urge that gave birth to them. In that sense, the album is rather impressionistic: portraying specific snapshots from Garm’s (the band’s frontman) state of mind, rather than providing a complete cinematic experience. Still though, the immersive nature of the music and its certain narrative edge is indisputable. Like any other Ulver release this one does not fail to envelop you in its own peculiar state of being.

The number of the songs itself reflects the more photographic nature of the music, as we have 11 songs for a 42 minute runtime, with the shortest cut being just under 3 minutes. An easy criticism would be to point to the lack of cohesion in the album and to write it off as chaotic and ad hoc. This couldn’t be less true, Neverland as any other Ulver album has a specific atmosphere of melancholia, which few other groups can capture that efficaciously. This record also conjures this aura of elusiveness and dream-like trance, which makes it easy for the band’s fans to enjoy it easily after familiarisation.

Especially, songs such as the opening ‘Fear in a Handful of Dust’, or ‘Horses of the Plough’, and ‘Pandora’s Box’ function as purely instrumental ambient pieces, merging arpeggiated synthesisers with field recordings, heavy droning synth chords, spoken-words, or even some tribal percussion work. ‘Elephant Trunk’ serves as a satisfactory comeback to the slightly spiritual atmosphere of Shadows of the Sun, with its first half’s centrepiece being a subtle piano lead, which then morphs into a beat driven slow-paced, glitch-laden ecstasy. ‘They’re Coming! The Birds’ also does feel like an electronic realisation of krautrock’s motorik hypnosis, particularly what is achieved on most repetitive moments of Neu!’s debut album.

My main issue with the record is its varying quality across the track list, for example ‘People of the Hills’ with its rhythmic lifted straight from an early 1990s acid house record feels at odds with the rest of the songs. Alternatively, some songs simply don’t quite live up to others. Case in point – ‘Weeping Stone’ seems to be leading up to something, but nothing really comes and we are left with a droning ambient piece consisting of underwhelming textures and a perceivable lack of sonic depth. Similarly, the last two closing tracks ‘Welcome to the Jungle’ and ‘Fire in the End’ simply do not catch my fancy as they flirt very closely with what is known as synthwave, a genre towards which I'm ambivalent at best.

As for other interesting influences and references, which I spotted, in my opinion Ulver went even further in the electronic rabbit hole and drew inspiration from what is nowadays known as progressive electronic. All the arpeggiated synthesisers and a good bulk of the spacy textures clearly evoke names like: Klaus Schulze, Mort Garson, Tangerine Dream, and Ashra. All of these artists coming firmly from the 1970s signifies that Ulver is adopting far broader influences this time. Well, who knows? Maybe we’ll get a meditative, instrumental space ambient record released under the Ulver moniker in a few years? A direction, which I’d honestly be very excited about.

To conclude, I’d like to stress one more parallel between the pioneers of progressive electronic of the 1970s and Ulver in 2026: world-building. Both Ulver and heavyweights of the Berlin School prioritise creating a specific atmosphere and successfully venture to lure, draw in, and then submerge the listener in their own sonic world. So, if immersion and holistic experience is what you value deeply in music, then with certainty I recommend their latest offering, as well as their whole back catalogue while we’re at it.