How Bowie's Blackstar Reinvented the 'final album'

By Julius Swinfen-Cranney

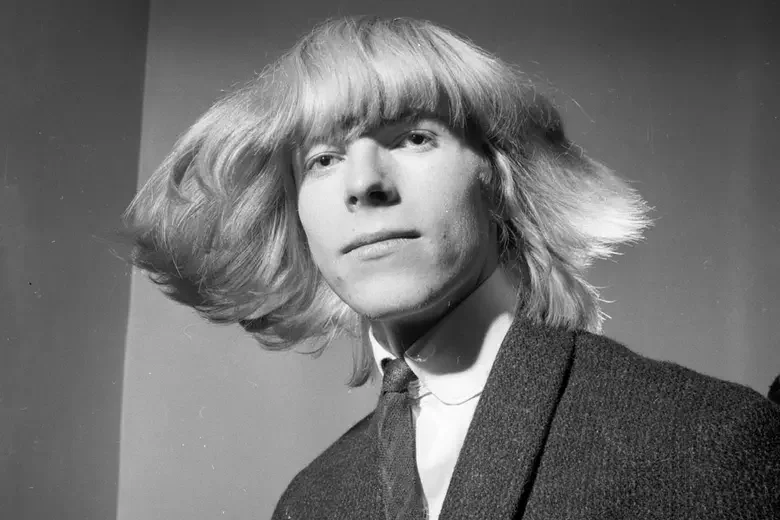

In a recent interview with the Hollywood reporter, actor Gary Oldman spoke on the passing of rock and roll legend and friend David Bowie: “don’t you feel that since he died, the world’s gone to shit? It was like he was cosmic glue or something. When he died, everything fell apart.” It’s been 10 years since the world lost the ever-reinventing artist that was Bowie. From his glam-alien, rock-star persona Ziggy Stardust, to ambient electronic textures of his Berlin trilogy, and a later push into experimentalism, Bowie defined his career on transformation and a refusal to stick to a single identity or sound. This was not any different by the time Blackstar rolled around. This was Bowie’s final album, released just two days before his death. But Blackstar was not just any old career retrospective album or something that looked to capitalise on the nostalgia of his earlier works, rather it was another reinvention for Bowie. It was an authored exit for a man who knew he was inevitably soon to die from cancer and a refusal to be bogged down by his looming mortality.

So what exactly makes Blackstar so different from any other swan-song album? Well you could say it’s the way that Bowie crafts the album around the aesthetic of death, instead of using the record to lament on life. The album is enigmatic and ominous, incorporating cryptic lyrics and an atmospheric blend of jazz, prog rock, and even some elements of hip-hop that was super experimental, even for someone of Bowie’s reputation. It touches on spirituality – the idea of transcending the material world – and is an exploration into the universal concept that we all, someday, must learn to let go. The album’s title track ‘★’ Bowie positions himself as a kind of mythic figure: “I’m a blackstar.” It’s a mantra that doesn’t appear to have any concrete meaning. Some point to the black star of theoretical physics, a transitional phase of a collapsing star that becomes an everlasting star of dark/vacuum matter; an astrological Lazarus. This idea rolls into Blackstar’s second track, ‘Lazarus’, which extends the spiritual transcendence metaphor; that song is more of an omniscient view on his own life and fame. In alchemy and esoteric mythology, the black sun/star is the initial stage of the Great Work, representing both an inner darkness and potential for transformation. There’s a clear kind of image that Bowie brews up here, but is done in a very cryptic way with these links to mythology and something metaphysical. It’s also interesting to note that black star refers to a type of cancer lesion, even if it is not the same type of cancer that Bowie was fighting. Blackstar’s obscurity shows Bowie’s reckoning with death and what his final album could be – a truth that life and art is not easily explained, but is meant to be felt and experienced.

Such a profound, bold final move at the end of Bowie’s career was bound to influence how other artists think about endings. This might not be a death in the literal sense, but a closing or death of a creative chapter. Just last year, Donald Glover released his final album under his Childish Gambino moniker, Bando Stone & the New World. The decision to give up the Gambino name mirrors Bowie’s understanding of identity as something that can be consciously created and consciously destroyed. Glover realised that this persona was no longer fulfilling to him, and that his priorities in life had shifted to other things: family, film and TV projects, and the everchanging landscape of the music industry. Coincidentally, Glover – much like Bowie – had to cancel his 2024 ‘New World’ Tour due to having a stroke, which only reinforced his desire to leave this chapter of his life behind. Glover makes apparent how Bando Stone is a final project as Gambino in a New York Times interview: “If people listen to this album, and it becomes a part of their identity, if they look back a year later and are reminded of how much they listened to it and what that felt like in the summer of '24 – that kind of real estate is way more valuable to me [than chart metrics].” Childish Gambino went out on Donald Glover’s own terms, allowing Glover to make a project he wished to be remembered for its artistic merit.

In a similar sense, the idea that artists can author their own ending becomes more striking when looking at artists whose lives ended prematurely. Take Mac Miller, and his final, posthumously completed album Circles. The project is quite sonically gentle, and finds Miller in a deeply reflective space. He grapples with personal growth and uncertainty, opting for more melodic singing, rather than dense, rapping to emphasise this contemplative mood. Intended to be paired with his previous record Swimming (joining to make the phrase ‘swimming in circles’), it’s clear that Miller had a clear vision for what this album was going to be, not knowing it would be his last. Producer and friend to Miller, Jon Brion, collaborated with Miller on Swimming and most of Circles, playing a large role in getting Circles up to scratch for its release. Around the album’s release, Miller’s parents put out a statement, on Miller’s instagram, stating: “Jon dedicated himself to finishing Circles based on his time and conversations with Malcolm [...] This is a complicated process that has no right answer. No clear path. We simply know that it was important to Malcolm for the world to hear it.” Similarly to Bowie, Miller’s death is something that will always be in the conversation surrounding his final album, but the shock and grief surrounding his death only elevates the heavy subject matter of Circles, rather than dampening the album’s excellence.

However, in all Bowie, Miller and Glover’s cases, it was the substance of the records, and the takeaway from their audiences, that mattered most. They are unified, not by sound or genre, but by a shared understanding of an intended ending. They show that, whether chosen, anticipated or tragically unforeseen, a ‘final album’ doesn’t have to be a pompous rerun of what came before or a nostalgic farewell. Blackstar changed an aspect of what music could be, as it almost reinvented how artists deliver a final, deliberate statement. So despite Gary Oldman being correct in many ways, that the world has “gone to shit” since Bowie’s passing, he’s also wrong. Without Blackstar, we would not see these incredible works made by incredible artists that reach their final creative peak.